The Oxenfeldt Principle

- Douglas T. Hicks CPA

- May 2, 2022

- 5 min read

Dr. Alred R. Oxenfeldt was eminent mid-twentieth century managerial economist, professor of business economics and marketing at the Columbia University Graduate School, and a long-time business consultant. In the early 1980s, I came across his book Cost-Benefit Analysis for Executive Decision Making: The Danger of Plain Common Sense published by AMACOM Books in 1979. The book contains many timeless insights into the creation of decision models and the use of cost information in supporting management decisions.

One of the simple, but powerful, observations in the book was his statement that, “An error in measuring the magnitude of an effect usually is far less serious than mistakes due to wholly overlooked consequences.” I’ve come to refer to this as “The Oxenfeldt Principle” and it has had major impact on the models I have created for my clients over the past four decades.

I like to explain the principle by telling the story of three racers who are about to compete in a 220-yard race blindfolded. Racer #1 is not told that the racecourse includes hurdles. Racer #2 is told there are hurdles, about how high they are and the approximate distance between them. Racer #3 is not only told there are hurdles, but their exact height and the exact distance between them. I then ask two questions: 1) Which of the three racers do you believe is in big trouble? 2) How big an advantage does Racer #3 have over Racer #2?

Obviously, Racer #1 is in the most trouble. Not knowing that there are hurdles will cause him to totally wipe out when he arrives at the first one. Knowing that there are hurdles, as well as their approximate height and distance between them, will give Racer #2 a substantial advantage over Racer #1. Racer #3’s advantage over Racer #2 will only be a slight one. Remember, they are all racing blindfolded so Racer #3 will not be able to capitalize greatly from the exactness of his information. Any error in Racer #2’s measure of the magnitude of the effect of having hurdles will be far less than the wholly overlooked consequences that haven’t been disclosed to Racer #1.

The Oxenfeldt Principle becomes important when modeling business processes that are important but are difficult to measure with a great deal of exactness. In such cases, a well-reasoned estimate of their effect will have far less serious consequences than ignoring them altogether.

For example, a US-based manufacturer produces products that it sells to companies throughout the world. Operating its shipping departments costs the company $300 thousand per year and it makes 7,500 shipments annually. That works out to $40 per average shipment. The company knows, however, that all shipments are not equal. Some require more physical and administrative effort than others and it would like to take that into account when measuring the cost of serving its customers.

It's first step is to identify what major factor makes processing one shipment more costly than another. After careful consideration it was determined that destination was the primary factor. Shipping to domestic customers required the least amount of work. Additional complexities made shipping to Canada and Mexico slightly more difficult. International overseas shipment required the greatest amount of work, a great deal more work. Being able to differentiate between these three types of shipments would provide them with valuable information.

They were not going to ask workers in the shipping department to keep track of the time they spent on each shipment. That would require too much time and cause administrative headaches. They understood, however, that an approximation of the differences would be much more valuable than ignoring them altogether, so they applied Oxenfeldt’s Rule. They accomplished this by applying the “weighting principle.” They gave each type of shipment a “weight” representing its relative difficulty. Domestic shipments required the least work, so they gave it a weight of 1.0. International North American shipments required about 50% more work, so they gave it a weight of 1.5. International Overseas shipments required considerably more effort, around four times more than a Domestic shipment, so they gave it a weight of 4.0. Using these weights, they incorporated the calculation shown in the following summary into their model:

In this manner they were able to differentiate between each type of shipment with a reasonable degree of accuracy. Oxenfeldt’s Rule enabled them to measure the cost of activities that would have been impractical to measure with greater precision.

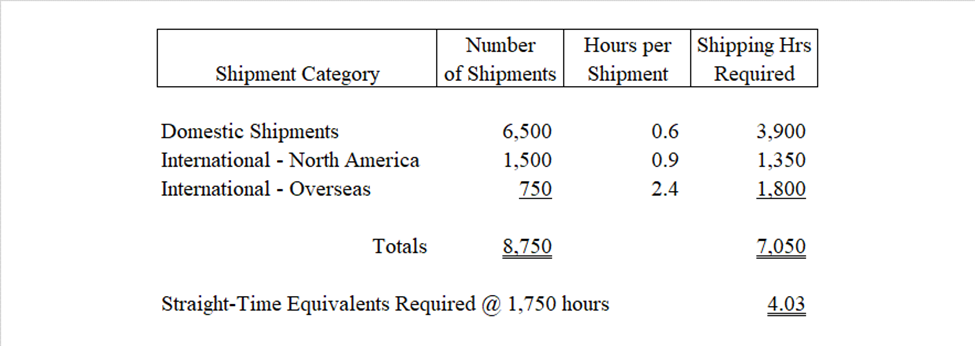

But effective models must also be predictive and that requires the projection of non-monetized resources. Oxenfeldt’s Rule applies to this process as well. Employees in the manufacturer’s shipping department worked 6,000 hours performing the department’s activities. As shown in the summary below, substituting hours worked for dollars of shipping department cost provides the company with an “hours per shipment” estimate for each category of shipment. After removing paid time off (vacation, holidays, etc.), as well as absenteeism, each full-time employee provides the manufacturer with 1,750 straight-time hours. This would indicate that the company needed 3.43 straight-time equivalent employees in shipping which coincided with the 15% overtime worked by shipping department employees during the year.

The resulting hours per shipment information could then be used to project the hours of shipping effort required to support various volumes and mixes of business.

For example, the manufacturer projected a significant increase in business during the coming year. This translated into an additional 1,500 Domestic shipments, 500 less International North America shipments and 250 more International Overseas shipments. Using the “hours per shipment” information generated by its model it could project the amount of work required in shipping as shown below:

In planning for the coming year, the manufacturer would have to provide for this additional work in shipping by either adding an employee or having the three current employees work 35% overtime. Once monetized, this would provide them with the projected labor cost of operating the shipping department during the upcoming year.

The manufacturer followed a similar process to project the cost of shipping materials (packaging, pallets, etc.) as shown below:

Using this information, they were able to project the cost of shipping materials for the upcoming years as shown below:

You’ll note that although the labor effort in shipping was projected to increase by 17.5%, the materials required to support shipping increased by only 4%. Labor was not the driver of shipping material cost and that fact was recognized in the model.

By heeding Oxenfeldt’s Rule and devising a simple, reasonably accurate method of measuring and projecting shipping costs, the manufacturer was able to avoid the consequences of either ignoring them altogether, or creating a cumbersome, complex system that was likely to be abandoned in the future.

By its very nature, modeling is an inexact process. It is important, however, to recognize all of the factors that can have a significant impact on the decisions made using the model. By incorporating Oxenfeldt’s Rule and devising simple, reasonably accurate methods of measuring processes that might otherwise be overlooked, an organization can accurately reflect the fundamental economics that underlie its operation and provide management with the accurate and relevant information they need to make economically sound business decisions.

Comments