Capacity Utilization and Product/Service Costing

- Douglas T. Hicks CPA

- Jan 28, 2022

- 2 min read

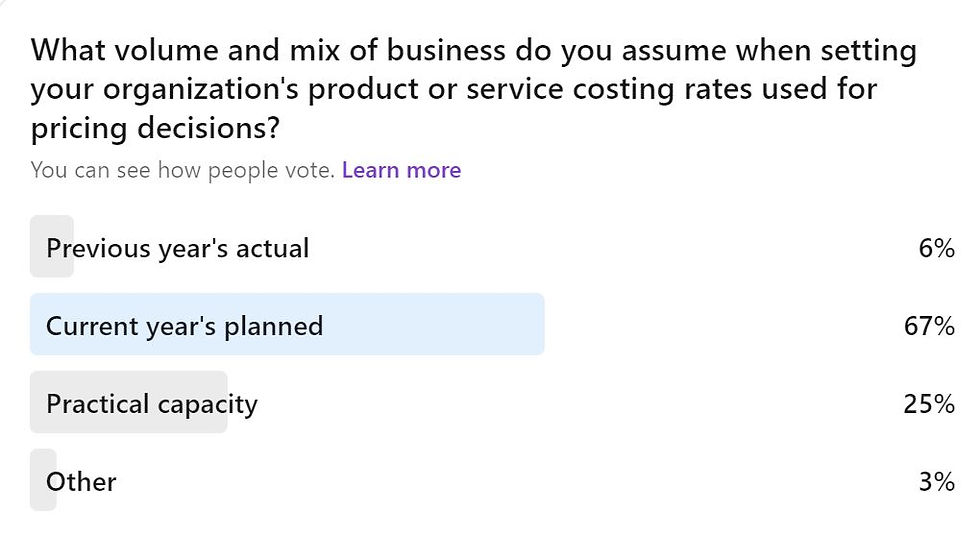

There were interesting results from PACE’s recent poll asking what assumed volume and mix of business organizations use when setting the costing rates they use when making pricing decisions. I was pleasantly surprised to see that only 6% indicated that they used the previous year’s actual volume and mix of business – its “actual annual activity.” That’s a method I still see used at many of the small and mid-sized organizations I encounter; an approach that leads some of them into “the death spiral” as falling volumes lead to higher rates which lead to higher prices which lead to lower volumes and so on.

The current year’s planned volume and mix was the most widely used base (67%). In accounting textbooks this approach is often referred to as “expected annual activity” and maintains that each year must stand by itself; that is, each year’s indirect cost must be applied to each year’s business. If the current year’s planned volume is significantly higher or lower than the organization’s normal volume this can lead to some of the same problems encountered by those using the previous year’s actual volume and mix. In reality, businesses operate on a continuum; months, quarters and years are arbitrary blocks of time that exist to facilitate the reporting of historical financial results. Using either “actual annual activity” or “expected annual activity” the calculated cost of any individual product or service can rise or fall simply because the volume of other products or services falls or rises.

“Practical capacity” was also a popular base with 25% of the poll’s participants indicating its use. Practical capacity is defined as the maximum level at which an organization can reasonably operate most efficiently. Such a base eliminates the year-to-year fluctuations inherent in actual or expected annual activity and acknowledges the fact that organizations operate on a continuum, but it also has its shortfalls. Practical capacity is often applied using a “rule of thumb” – like “80% of two shifts five days a week” or “85% of three shifts six days a week” – for each of the organization’s individual activities. Most facilities, however, have key or bottleneck activities that reflect the rule of thumb, but then have ancillary or secondary activities that operate below that level. In addition, it is unlikely that the organization will actually be operating at its practical capacity for an extended period of time.

Perhaps the most appropriate base for developing costing rates for pricing decisions is what is often referred to as “normal activity” – the level of capacity utilization that will satisfy average consumer demand over a span of time (often five years) that includes seasonal, cyclical, and trend factors. This base recognizes that businesses operate on a continuum, reflects the actual levels of each business activity over time, and eliminates the year-to-year fluctuations that can distort management’s long-term understanding of product, service, or customer profitability.

Personally, I prefer using normal activity as a base. What do you think?

Comments